What does it take for a woman to become a writer? To devote herself to her craft? To turn inward and pull the words out of the murky depths that only she can plumb?

This question has haunted me all of my adult life. It’s the question that sent me to graduate school, where I was determined to discover exactly when and how American women writers had found the space and courage to become that most selfish—and thus most unladylike—of things, an artist. And even though I wrote a book about the post-Civil-War generation of women writers who had done exactly that, as well as biography of the most committed and accomplished of those women—Constance Fenimore Woolson—in addition to a book and many articles about Little Women and the ambitions of Jo March, I am still searching for answers.

The only difference now is that I want to answer that question for myself—finally. I’ve put it off long enough.

As I wander around Europe in search of experiences and opportunities to grow, I struggle to write or even to think of myself as a “writer.” I also struggle to imagine what my future could look like. I’ve had some vague dreams of myself in a cottage, drinking tea and writing all morning, then going for long country walks in the afternoon. A peaceful, centered life, like the one Woolson had for the years she lived on the hill of Bellosguardo looking out over the valley and the rooftops of Florence. She loved being above the fray and the social whirl of the town. She loved her hours-long walks and her solitude. I felt all of that when I stood in her living room and looked out over that stunning view in 2012. But I also know that she struggled with her solitary life.

In 1884, after reading George Eliot’s Life as Related in Her Letters and Journals, Woolson made a sobering observation about the advantages Eliot had enjoyed:

“She had one of the easiest, most indulged and ‘petted’ lives that I have ever known or heard of. . . . True, she earned the money for two, and she worked very hard. But how many, many women would be glad to do the same through all of their lives if their reward was such a devoted love as that!” (CFW to Emily Vernon Clark, n.d., in The Complete Letters of Constance Fenimore Woolson, edited by Sharon Dean, 550–51.)

That line has stuck with me, and I thought of it immediately as I wrote the words “What a Woman Writer Needs” at the top of this page. Like Woolson, I am now alone and wondering how to make a living and to write what matters to me. I’ve been thinking of Woolson a fair bit lately. I can see now that I was so drawn to her story because she did exactly what I secretly wanted to do—leave the U.S. and make her life in Europe. Without a doubt, she found it easier to be a writer in England and Italy, her primary abodes, during the 14 years she lived abroad. Part of it was that she could live more cheaply, but another factor was that as an American woman, she could live pretty much however she wanted in these foreign contexts. It was easier to live an unconventional life as a woman in Europe than at “home.” To be honest, though, Woolson no longer felt as if she had a home. She came to Europe after her mother died, her last responsibility. And I suppose I did something similar, leaving after my daughter went off to college.

It's also not lost on me that I am precisely the age Woolson was when she (most probably) decided to take her life. (Don’t worry, I don’t plan to follow in Woolson’s footsteps to that extent.) She had run out of hope that she would be able to continue to live without a home, without sufficient financial resources, and without the support of family or spouse (although she felt conflicted about those entanglements). Her health was also failing her. Writing those long Victorian novels by hand was a strenuous task that riddled her with pain. A bout of the flu weakened her, and she appears to have become addicted to laudanum, which her doctor refused to give her any more of, but without which she could no longer sleep. So there were many extenuating factors.

Woolson and James: Two Solitary Souls

In December, when I went to Rye to see Henry James’s home, Lamb House, I thought a lot about Woolson, her friendship with James, and how deeply he grieved her death. (He moved there three years after she died.) I saw in an old photograph of his study that he had a picture of her prominently displayed on his wall. (She is to the left of the fireplace at the top of that middle row. It’s hard to see, but it is one of the most well-known images of her, published in Harper’s.)

His biographers have analyzed the works that were influenced by his memory of her, and I wrote at length in my biography about “The Beast in the Jungle” (1903), which he likely wrote at Lamb House. Once, he even imagined how happy she might have been there, too. Here is what I wrote:

“Six years after her death, James reflected on his good fortune, living in Rye, England, where he enjoyed financial independence and the comfort of owning his own home, conditions which enabled him to return to writing the novels that would secure his reputation as the “Master.” After a visit from Grace Carter, he wrote to her, “You give me great pleasure—more than I can say—by expressing to me your sense of our common memory of, & common affection for, our C. F. W. But how she (in spite of Venetian lures & spells of illusions) would have liked this particular little corner of England, & perhaps found peace in it.” He couldn’t help but imagine her there as well, living in the atmosphere of settled tranquility she had craved.” (Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist, p. 317)

As I wandered around the largely empty rooms and garden of Lamb House, I couldn’t help but feel the presence of his memory of her and, even more, his feeling that she could have found peace there, too. He had many guests over the years, including Edith Wharton, who came frequently. But I can’t help but feel that James implied more than simply having Woolson as a guest. As I discuss in my biography, they lived under the same roof for a while when she was up on the hill of Bellosguardo, and they had entertained the possibility of some kind of collaboration not long before she left England for Venice, where she would take her life within the year.

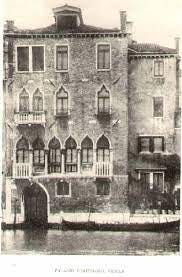

Casa Semitecolo, Woolson’s last “home”

The fact was, and James knew it, that Woolson had run out of strength to carry on, in the absence of the comfort of a home and the support of a companion, such as he might have been able to offer her after he moved to Lamb House. Of course, we all know that James was gay, and I don’t believe that Woolson had romantic fantasies about marrying him. But they were indeed quite close, like family—quasi-siblings, I call them. As they grew older, they could have at least lived near each other and provided the kind of mutual support that would have surely benefitted both of them. But it’s also true that they were both wary of the responsibilities that domestic partnership would entail. They had managed to live quite comfortably in separate apartments in her house in Italy, though, and surely could have again, had tongues refrained from wagging.

A Solitary Writer’s Life

It’s been a long time since I first mulled over all of this, but it has a greater resonance for me now, as I see my life converging with Woolson’s in some ways. I don’t relish the thought of living a celibate, solitary life, nor having to make money from my writing, as she did.

As I was writing Woolson’s biography (not needing to make a profit from it, since I was a professor), my life was quite different than it is now. Although I wouldn’t say I’ve ever experienced the loving devotion George Eliot did (from two men!), I did have the stability and grounding of a family and a stable home. I didn’t have to worry about paying the rent or the grocery bill (thanks to my husband’s salary and funding from the NEH). I had a room all to myself in which to write, and quiet in the house during the day. And most importantly, I think, I had to stop writing everyday at 3:00 so I could leave to pick up my daughter from school. She enriched my life in ways that are even more apparent to me now that I don’t see her every day.

As much as women struggle to maintain their own creative projects and energies in the face of motherhood, which I did as well when she was young, I also found that her presence in my life made it fuller and more fulfilling in a way that writing never could. The two satisfied different but perhaps complementary needs—the need for mental stimulation and self-expression on the one hand, and the need for human bonding and attachment. (I also know that having one child, as opposed to a plethora, enabled me to create that balance in my life. See Alice Walker’s essay, “One Child of One’s Own.” You can see part of it here.)

Louisa May Alcott never married or had children, so she could only speculate that a husband and a bunch of rambunctious boys could make Jo March a better writer someday. Jo says in Little Women’s final pages, “I haven’t given up the hope that I may write a good book yet, but I can wait, and I’m sure it will be all the better for such experiences and illustrations as these,” referring to her family and the school she and Professor Bhaer run.

The first time I read Jo’s words, when I was in graduate school, I hoped they could be true, because I desperately wanted a career and a family. I got what I wished for, and for years I felt that I could never give 100% to either, but it was actually the balancing act between the two that sustained and nourished me. Now I often feel like my life is out of whack, and I find myself craving loving companionship and the groundedness of a home. I wonder, if I had that, could I then find the mental capacity to dive back into my novel?

I had an interesting talk the other day with the writer and writing coach Cynthia Morris, and she told me that although travel is a major inspiration for her, she is never able to write while she is on the road. There is too much to see and do, too much going on, to write much more than one’s fleeting impressions in a journal. I think of Wordsworth’s words about poetry being the “overflow of powerful feelings . . . recollected in tranquility.” What does a writer need to feel that tranquility? A home and a wife, you might say, someone to take care of life’s daily tasks, as so many men like Wordsworth have had. But I think what we need is more than just someone to feed us and keep the house clean.

As Cynthia said (I believe it was her—my apologies if it was someone else), women tend to be relational beings. We seek community and companionship and can have a hard time venturing off into the unknown—as solo travelers or as writers living in solitude. That doesn’t mean there haven’t been plenty of powerful women writers who’ve praised solitude and have sought it particularly as an antidote to the self-sacrifice to which women are so often conditioned. (Here is one great piece about Elizabeth Bishop and solitdue sent to me by my friend, the writer Patricia Henley.) I know that I needed some time apart from responsibility to family to begin to see myself again, so lost had I become inside of the matrix of other people’s needs and emotions. But having spent a fair bit of time alone now, I feel myself tipping too far in the other direction at times.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot—the basic human need we have to love and be loved, and to have devotions and interests outside of our own heads. For writers, I think this is important, even as we tend to crave solitude. I struggled when I was at the Dora Maar House in Provence.

The Dora Maar House, the big one in the middle.

I finally had long stretches—whole days, even—to think and write. I’d craved that for so long. But once I had it, I struggled to get through the day. I felt depressed and anxious. I think a big part of it was that I didn’t have anything solid to anchor me, like a home and family to return to. If I had, I might have missed them, but I don’t think I would felt the kind of nagging panic that sometimes haunted me there.

Will my life always be like this, I wondered? Will I have whole days when I don’t speak to another soul? Will I be trapped in my own head for long periods of time? Will I live like Dora Maar did, alone, solitary, nun-like, for the rest of my life? She continued to paint and late in life she returned to photography for a bit. But she found her greatest purpose and solace in her religious fervor. (She could only get over Picasso by replacing him with God, her biographer has claimed.) Most people believe that she lost her creative spark after Picasso, although clearly he was not the kind of supportive companion who allowed her to thrive as an artist. I couldn’t help feeling that her solitary life forever changed her art, which increasingly reflected the loneliness she undoubtedly felt.

From Bonjour Paris

Community and Companionship

Of course, Virginia Woolf has the most famous answer to the question of what a woman needs to be a writer—a room of her own and an independent income. She doesn’t mention a home (which must contain the room) or a companion to provide ballast and support, which she most certainly had with her husband, Leonard. I feel much like Woolson did, though—wary of giving up my independence in exchange for security and grounding. Another possibility has also been floating around in my head—a community of women, which is, interestingly, what Alcott proposed at the end of her adult novel Work.

I realized recently that I first started having thoughts about welcoming other women writers into whatever home I might create back in 2019. I can’t remember the name of the memoir I read then, but it was the memoir of a woman (a writer) who had had her life upended by an unexpected divorce and bankruptcy. Once she was on her feet again and had bought a new home, she invited her writer friends to come and stay, to have a writing retreat in her basement guestroom. As a result, she often had a guest staying with her, and they would each spend their days on their respective work and then come together and make dinner and have enriching conversations in the evening. Doesn’t that sound lovely?

It makes me think of the life Woolson had at Bellosguardo, which I realize as I write this wasn’t as solitary as I’ve made it sound. Those were the happiest times of her life, when she lived in a big house by herself with a beautiful view but had some dear friends nearby with whom she found the artistic community and companionate affection that she needed. The composer Francis Boott and his daughter Lizzie, an artist who was married to the painter Frank Duvenek, became dear friends.

But it all fell apart when Lizzie died not long after giving birth to a child and Francis and Frank decided to take the baby back to the U.S. to be near relatives who could help raise him. Woolson was left behind, bereft and increasingly depressed, until she decided she had to leave as well. The ghosts of so much former happiness haunted her. After years of more or less wandering, she settled into an apartment on the Grand Canal in Venice, where she unpacked her furniture, paintings, books, and keepsakes from the Boots for the first time since she left Bellosguardo. She died among her memories of having once in her life lived in a nourishing community. That is what she needed, I believe, more than some kind of partnership with Henry James.

As I write this on the train to Inverness through the Highlands opening out in front of me, I continue to contemplate what kind of life I want to build for myself. My dream is for a life that will support my writing and provide the human companionship I crave as much as the time and space to put my thoughts down on the page.

A view from the train

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the matter. Do you find yourself dreaming of another way of living? Do you find that you need more solitude or more companionship in your life? What do you think a (woman) writer needs in order to fulfill her creative potential?

Until next time,

Anne

I've been thinking about community and writing (and other artforms) lately, as I recently wrote an article about Flannery O'Connor's artistic community. People often think of her out in the middle of nowhere, writing away at Andalusia in Milledgeville, and it's true that her solitude (and daily structure of mass and her mother's providing cooking and cleaning and a house) allowed her to work regularly. However, she had quite a network of friends and fellow writers--before her diagnosis with lupus, she lived with Robert and Sally Fitzgerald in a set-up similar to what you describe. She lived and worked in their garage apartment in exchange for looking after their children. They would all have dinner together. As Robert was working on a translation of Oedipus at the time, their discussions of their work over dinner crept into O'Connor's work--you can see the Oedipus themes in Wise Blood, that she was writing at the time.

Something I'm writing about right now is how often women are a part of the invisible infrastructure necessary for art to happen (in music scenes, especially. Bookers, photographers, fans, office workers--these are often the necessary behind-the-scenes roles often filled by women). But I'm also realizing that a feeling of community is also something that I crave. But I want a balance between solitude for creation and connection with others involved in creation. (In fact, the words I chose for this year are creation and community.)

(Thank you for such a thought-provoking post!)

I'm so glad to have found your newsletter, Anne! I think we have very similar interests in our research and writing studies. Looking forward to learning more about your work (and your travels :)